Love Diane Arbus: Check out her work here:

11 Lessons Diane Arbus Can Teach You About Street Photography

"(All photographs copyrighted by the Estate of Diane Arbus)

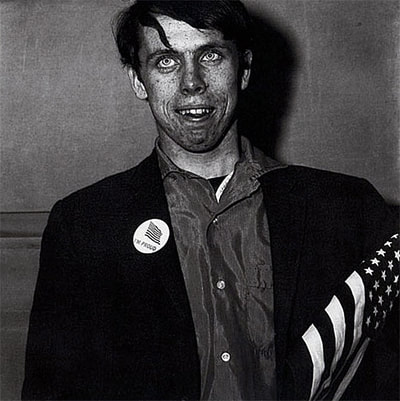

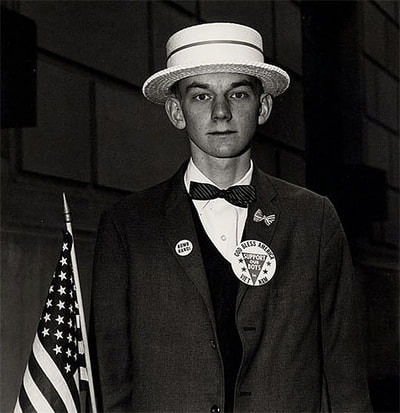

Diane Arbus is a photographer that has a very profound impact on me. When I first saw her photograph of the “grenade kid” — it hit me in the chest and has burned itself in my mind ever since. Upon studying more of Diane Arbus’ work — I found her photographs to be very applicable to my interest in shooting street photography of strangers- mostly as a mode of portraiture.

There is a wealth of knowledge on Diane Arbus (several memoirs, books, and even movies have been made on her), and I cannot say I am an expert on her work. However here is some golden knowledge I have found from one her books published by Aperturethat I found incredibly insightful that I wanted to share with you." http://erickimphotography.com/blog/2012/10/15/11-lessons-diane-arbus-can-teach-you-about-street-photography/

1. Go places you have never been

2. The camera is a license to enter the lives of others

3. Realize you can never truly understand the world from your subjects eyes

4. Create specific photographs

4. Adore your subjects

5. Gain inspiration from reading

6. Utilize textures to add meaning to your photographs

7. Take bad photos

8. Sometimes your best photos aren’t immediately apparent (to you)

9. Don’t arrange others, arrange yourself

10. Get over the fear of photographing by getting to know your subjects

11. Your subjects are more important than the pictures

Biography: Diane Arbus

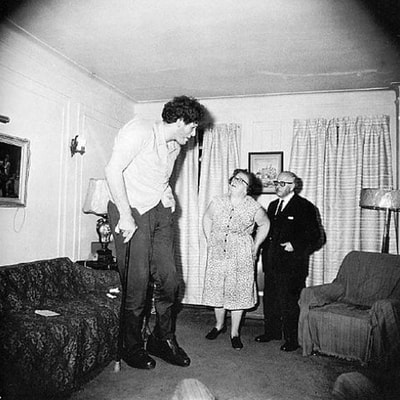

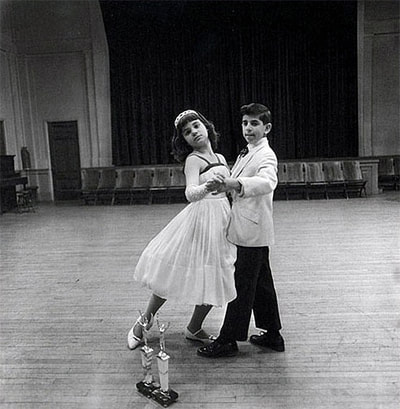

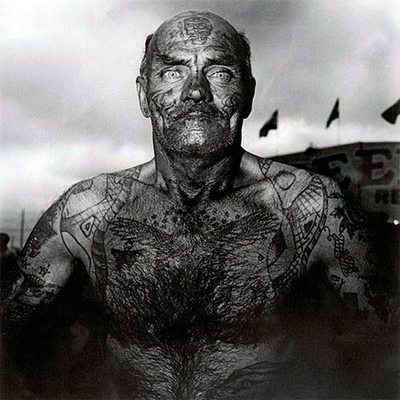

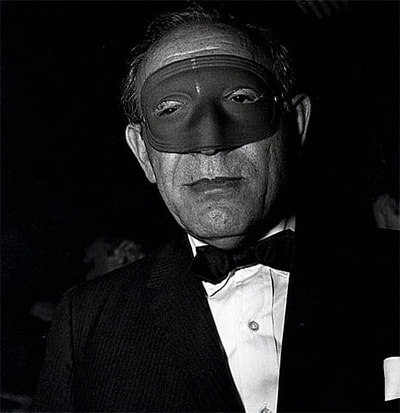

Diane Arbus changed how the world looks at photographs and how photographs look at the world. Best known for her pictures of “freaks” and eccentrics such as “The Jungle Creep,” “The Marked Man,” and nudists, she also changed the world of children’s fashion photography and celebrity photography. She was alternately described as shy, sweet and girlish or coldly aggressive and ”as tough as any man” in her field. Friends and colleagues were amazed by her ability to relate to her subjects, her openness and vulnerability with them. On the other hand, some people who posed for her found her to be manipulative, bossy, and cold. In a 1985 article titled “The Hostile Camera,” Calvin Bedient said of her: “She is a modernist heroine, braving the dark places of psychology, her only shield her camera, an eye that would not flinch.”

Diane was born on March 14, 1923, to Gertrude and David Nemerov. She was the second of three children, between elder brother Howard and younger sister Renee. All the Nemerov children grew up surrounded by the trappings of wealth and success. Their maternal grandparents started the Russeks fur stores their father now ran. Their only contact with their father’s side of the family (the poor immigrant Nemerovs) was when they would spend Passover in Brooklyn with David Nemerov’s parents. Later in life, Diane would frequently refer to the atmosphere of wealth in which she grew up. “I was confirmed in a sense of unreality. All I could feel was my sense of unreality,” she told interviewer Studs Terkel (in 1969) Her later career could be summed up as a constant search for the “reality” she was forbidden to see as a child.

Diane and her siblings attended the Ethical Culture School and the Fieldston School, both in Manhattan. At fourteen, Diane met nineteen-year old-Allan Arbus, who was working in the Russeks art department. They immediately fell in love and became intensely involved with one another. Though her parents tried to discourage the affair, (much as her grandparents had tried to stop her parents), Diane and Allan continued to meet clandestinely for the next four years. On April 10, 1941, when she was just eighteen, Diane and Allan Arbus were married by a rabbi. Her parents, faced with this fait accompli, gave their blessing to the marriage. The Arbuses were married for twenty-eight years, although they separated after nineteen, and had two children, Doon and Amy.

In 1946, after Allan returned from World War II, the couple decided to pursue a career as fashion photographers. David Nemerov gave them their first job, the account with Russeks Furs. Over the next ten years the Allan and Diane Arbus Studio became very successful, with Diane conceiving the style of the shoot and Allan handling the technical side. Allan, for his part, always encouraged Diane to take her own pictures and pursue her own creativity. Diane herself credited Allan as being “my first teacher.” However, Diane hated the world of fashion photography and began to suffer increasingly from depression (as had her mother). In 1957, she quit styling the Arbus Studio photo shoots.

Moving into the world of independent photography was not easy for her. Diane Arbus was extremely shy, which hampered her ability to approach strangers on the street to ask them to pose. In addition, pursuing her own career went against the model of women at the time. As her daughter Amy has remarked: “Ma had always thought all her life was about helping Pa do his thing. It took her a long time to adjust.”

By 1960, Diane and Allan Arbus had separated, though Allan continued to be a major emotional support in her life. He also continued to assist Diane with her photography and taught her the technical side of the art.

To develop herself as a photographer, Arbus first enrolled in Alexey Brodovitch’s workshop, but she quit soon after she started. Her next attempt was more successful. In 1958 she enrolled in Lisette Model’s class at the New School. In Model, Arbus found her mentor and a lifelong friend. Model helped her identify and accept what subjects she wanted to photograph—what Doon Arbus later called “the forbidden.” Art critic Peter Bunnell has said that Arbus “learned from Model that in the isolation of the human figure one can mirror the essential aspects of society.”

In 1959, she met her second mentor, Marvin Israel, and he quickly became one of the major influences in her life. He supported her ideas and pushed her to pursue them even further. He advised her on which photograph to choose from a contact sheet and introduced her to people he thought would influence her or help her career. In 1961, he became the art director of Harper’s Bazaar and was able to publish her work as well.

Perhaps because of Model’s and Israel’s support, Arbus began to use her fear as opposed to being frozen by it. Throughout the rest of her life she would talk of her photography as an adventure and the fear as a stimulus. Her biographer Patricia Bosworth notes, “Her terror aroused her and made her feel; shattered her listlessness, her depression. Conquering her fears helped her develop the courage she felt her mother had failed to teach her.” Driven by her curiosity and fear, Arbus began to haunt the places that would define her as a photographer: Hubert’s Freak Museum in Times Square, Coney Island, gay nightclubs, and the tenements of Brooklyn and Manhattan. She began her life as a self-described “collector,” viewing her work as “a sort of contemporary anthropology.”

In the late summer of 1959, Arbus took her portfolio to Esquire magazine and showed it to Harold Hayes, the articles editor. Hayes was “bowled over by Diane’s images. … Her vision, her subject matter, her snapshot style were perfect for Esquire, perfect for the times; she stripped away everything to the thing itself. It seemed apocalyptic.” A few months later, Arbus was asked to do a photo essay on the nightlife of New York for a special Esquire issue on the city, published in July 1960. It contained Diane Arbus portraits of six “typical” New Yorkers, titled “The Vertical Journey: Six Movements of a Moment Within the Heart of the City.”

“The Vertical Journey” marked the beginning of her career as a solo commercial photographer. Over the next eleven years Diane Arbus would publish over 250 pictures in more than seventy magazine articles. Her most frequent supporters in the publishing world were Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, and two London publications, the Sunday Times Magazine and Nova. Her work also appeared in New York, Show, Essence, the New York Times, Holiday, Sports Illustrated, and the Saturday Evening Post.

Throughout her career Diane Arbus hoped to break the pattern that bound most photographers. She tried to make a living from magazines while still maintaining her integrity and pursuing her style and interests, and to some degree she succeeded. Her serious art work and her magazine work were never as separate and distinct as that of most other photographers.

As the magazine assignments and her friendships with Lisette Model and Marvin Israel began to help Arbus feel more confident, she developed her own singular approach to photography, both artistically and technically. In 1962, Arbus changed her camera from a Leica to a Rolleiflex. The negatives were less grainy and gave her the clarity she wanted. The square frame of this new camera became a signature of her later work. In 1964, she began using a Mamiya C33 camera along with her Rollei. She used the Mamiya with a flash, which gave her subjects the exposed and vulnerable look that became another signature of her style. By 1970, she was taking photographs with a Pentax.

In 1965, three of Arbus’s early pictures were included in a show at the Museum of Modern Art called “Recent Acquisitions.” Arbus was hesitant and concerned, as she would be throughout her career, about the public’s reaction. She was right. Yuben Yee, the photo department’s librarian, would come in early every morning to wipe the spit off the photos. When Arbus learned of this, she left town for several days. As Yee said, “People were uncomfortable—threatened—looking at Diane’s stuff.”

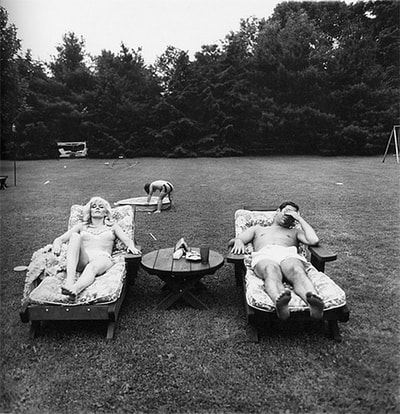

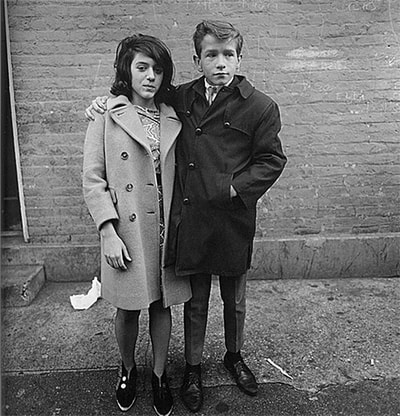

Over this period, Arbus was getting work from magazines to do portraits of the famous and a few children’s fashion shoots. She also received two Guggenheim Fellowships, in 1963 and 1966, to pursue her private work. While still taking photos of “freaks” and eccentrics, she was moving into other areas of identity. She began taking pictures of twins and triplets, of families and couples in Central Park, of the uptown and downtown art scenes and of nudist camps.

In 1967, the Museum of Modern Art asked Arbus to contribute to “New Documents,” a major exhibit of modern photography. Again, she was hesitant about putting her work on public display. At the same time, she became tremendously excited by the possibility for future work, which she hoped the exhibit might generate.

The critical response was generally positive, although Chauncy Howell of Women’s Wear Daily called it “grotesque.” Robert Hughes of Time said, “Arbus is highly gratifying.” In the New York Times, Jacob Deschin wrote, “Even her glamour shots … look bizarre. … At the same time there is occasionally a subtle suggestion of pathos, now and then diluted slightly with a vague sense of humor. Sometimes, it must be added, the picture borders close to poor taste.”

Unfortunately, although the “New Documents” exhibit did bring Arbus to the attention of the London Sunday Times Magazine, her fear that the exhibit might lead to the public misunderstanding her work was realized. With the notoriety of the “New Documents” show, Diane Arbus became more firmly established as the “freak” photographer, and publishers became increasingly shy of using her to photograph the subjects of their stories. A further blow to her commercial career came with the controversy over the “Viva pictures.”

In December 1967, Arbus was hired by the newly created New York magazine to photograph the actor Viva. Arbus ultimately gave the magazine several nude photographs of Viva, which were published in the April 29, 1968, issue. Viva, who felt she had been misled and lied to by Arbus, threatened a lawsuit but later dropped it. The public and advertisers were so upset that the magazine lost over a million dollars in advertising, most of which never returned to the publication. Journalist Tom Morgan says that those pictures were “watershed pictures. They broke down the barriers between private and public lives.”

In 1968, she was hospitalized with hepatitis. (She had suffered from it before, in 1966.) Weakened from the illness, she felt that she was losing her strength and independence. She became increasingly depressed. In 1969, her marriage to Allan Arbus was formally ended by divorce and the Arbus Studio was closed.

By 1970, Diane Arbus had become a legend among young photographers. She was teaching classes and workshops and giving lectures—generally not something she enjoyed, but she was in demand and needed the money. That year she won the Robert Levitt Award from the American Society of Magazine Photographers for outstanding achievement. She also began what would be one of the final projects of her career, taking pictures of mentally retarded adults at a home in Vineland, New Jersey. At first these photos seemed to exhilarate her, but soon she grew to hate the Vineland pictures, because she felt that the shots were “out of control.”

Beyond her dismay over those photographs, there was the attention brought on by success. The May 1971 issue of ArtForum had published a portfolio of her pictures. Walter Hopps of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., had persuaded her to agree to exhibit her work at the Venice Biennale in the summer of 1972. These projects only seemed to panic and depress her further. “She did say over and over again that now that she was getting better known people expected things of her and she didn’t want anyone to expect things from her since she didn’t know what to expect from herself and never would.”

Suffering from extreme depression, caught between her fear of fame and her need for money, and at a crossroads in her work, Diane Arbus committed suicide in her apartment on July 26, 1971, leaving the words “last supper” written across that date in her journal. Marvin Israel discovered the body on July 28.

A posthumous exhibit was mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972, then traveled around the United States and Europe. In 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of New York mounted a major, comprehensive retrospective exhibition, entitled “Diane Arbus Revelations.” Since her death three books of her photographs have been published: Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, Diane Arbus: Magazine Work, and Untitled. For many years she remained a cult figure, and it was not until the 1980s that her work came to be generally accepted. Her impact and influence will never again be considered marginal. She changed not only photography but how we identify each other as human beings.

BibliographyArbus, Doon, and Marvin Israel, eds. Diane Arbus: Magazine Work (1984); Bedient, Calvin. “The Hostile Camera: Diane Arbus.” Art in America (January 1985); Bosworth, Patricia. Diane Arbus (1984); Bunnell, Peter. “Diane Arbus.” Print Collectors Newsletter (January/February 1973); Deschin, Jacob. “People Seen as Curiosity.” NYTimes, March 5, 1967, sec. 2, p. 21; Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (1972); Morgan, Susan. “Loitering with Intent: Diane Arbus at the Movies.” Parkett 47 (1996); NAW modern; Spring, Justin. “Diane Arbus.” ArtForum (February 1992).

11 Lessons Diane Arbus Can Teach You About Street Photography

(All photographs copyrighted by the Estate of Diane Arbus)

Diane Arbus is a photographer that has a very profound impact on me. When I first saw her photograph of the “grenade kid” — it hit me in the chest and has burned itself in my mind ever since. Upon studying more of Diane Arbus’ work — I found her photographs to be very applicable to my interest in shooting street photography of strangers- mostly as a mode of portraiture.

There is a wealth of knowledge on Diane Arbus (several memoirs, books, and even movies have been made on her), and I cannot say I am an expert on her work. However here is some golden knowledge I have found from one her books published by Aperturethat I found incredibly insightful that I wanted to share with you.

Diane Arbus is a photographer best known for her square-format photographs of marganlized people in society — including transgender people, dwarfs, nudists, circus people. Although she has always expressed love for her subjects, her work has always been controversial and critiqued heavily by art critics and the general public for simply being “the photographer of freaks” and casting her subjects in a negative light.

Arbus studied photography under Berenice Abbott, and Lisette Model, during the period when she started to shoot primarily with her TLR Rolleiflex in the square-format she is now famous for. Most of her photographs are shot head-on, mostly with consent, and often utilizing a flash to create an surreal look.

Arbus was born in 1923, and it shocked the entire photographic community when she committed suicide in 1971 (at the age of 48). It was reported that she did experience many “depressive episodes” during her life.

Although it has been around 40 years since her passing, she has influenced countless photographers (including myself) and there is still much work being published on her life. In 2006, Nicole Kidman played as Diane Arbus in the motion picture “Fur” — a fictional version of her life story. Also recently published (2011) a psychotherapist named William Schultz published a biography on Arbus named: “An Emergency In Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus“.

Lessons from Diane ArbusAll of the excerpts used in this article were from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, in which she shares her thoughts in interviews and writings. You can see an entire selection of the text here:

1. Go places you have never been

When it comes to street photography, I feel one of the greatest joys is that it allows you to experience life in a novel and different way. Arbus shares some of her thoughts:

“My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been. For me there’s spending about just going into someone else’s house. When it comes time to go, if I have to take a bus to somewhere or if I have to grade a cab uptown, it’s like I’ve got a blind date. It’s always seemed something like that to me. And sometimes I have a sinking feeling of, Oh God it’s time and I really don’t want to go. And then, once I’m on my way, something terrific takes over about the sort of queasiness of it and how there’s absolutely no method for control.

I feel that one of the greatest traits that a street photographer has is his or her curiosity. Street photography gives us the wonderful opportunity to have the excuse to go to places we generally don’t go — in order to look for interesting photographs and experiences.

Takeaway point: Explore and take the path off the beaten road. If you always shoot street photography in the same place, venture off elsewhere and go down hidden paths that you haven’t been down before. Realize that there is little you can control in terms of what subjects appear, how your background will look at a given time, and how the weather will be for your shots. Simply let the shots come to you, and embrace them.

2. The camera is a license to enter the lives of others

In street photography, we are often timid to approach random strangers and ask to take photographs of them. After all, it may seem weird for us to simply approach someone we don’t know.

However consider how much weirder it would be to approach a stranger without having a camera and having a reason to talk to them. Having the camera is a license to enter the lives of others, as Arbus explains:

“If I were just curious, it would be very hard to say to someone, “I want to come to your house and have you talk to me and tell me the story of your life.” I mean people are going to say, “You’re crazy.” Plus they’re going to keep mighty guarded. But the camera is a kind of license. A lot of people, they want to be paid that much attention and that’s a reasonable kind of attention to be paid.

Arbus also continues by sharing the idea that many people are quite humbled by being paid a ton of attention by having you want to take their photograph.

Takeaway point:Don’t be embarrassed by your camera and try to hide it when shooting on the streets. Embrace it, and use it as a tool to help you get a license to enter the lives of others. If you see someone on the street that you find interesting and want to get to know more about them — approach them and start chatting with them and explain that you are a photographer and you would like to take their portrait for a project you are working on. Most people become quite humbled by this, and are generally excited to be part of the project.

If you want to take a photograph more candidly, go and take the photograph without permission and then afterwards — explain why you took the photograph. Tell them what project it is for, and what unique part of them that you found that you wanted to capture. When you explain why you think that people are interesting and why you wanted to take a photograph of them, people are generally humbled by that.

3. Realize you can never truly understand the world from your subjects eyes

As a photographer, it is easy to see things from our own perspective. However it is difficult to see the world from your subjects perspective (if not impossible). Arbus explains that although we can try to give our best intents in getting to know our subjects well- our photographs will not always show what we intended. You might have a certain intent when photographing, but the result can be totally different. Not only that, but what we may perceive as a “tragedy” may not be considered as a tragedy to your subject:

“Everybody has that thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way and that’s what people observe. You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw. It’s just extraordinary that we should have been given these peculiarities. And not, content with what we were given, we create a whole other set.

Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you.

And that has to do with what I’ve always called the gap between intention and effect. I mean if you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic. You know it really is totally fantastic that we look like this and you sometimes see that very clearly in a photograph. Something is ironic in the world and it has to do with the fact that what you intend never comes out like you intended it.

What I’m trying to describe is that it’s impossible to get out of your skin into somebody else’s. And that’s what all this is a little bit about. That somebody else’s tragedy is not the same as your own“.

Arbus took a lot of photographs of marginalized individuals in society (transgender, dwarfs, circus people, etc) and of course she had her natural prejudices when she took photographs (as well all do). Her individuals would try to present themselves to the world in a certain way, but other people might perceive them in a different way.

For example, if someone dressed up as a rockstar with chains and spiked studs, they may feel that they are giving off the image that they are powerful and cool. However an outsider might see this as frightening, and something abhorrent.

Takeaway point:Realize that it is impossible to truly get into the mind of someone else. When you are photographing someone in the streets, there is no way to know their entire life history or their character. Sure you might perceive them to be a certain way on the outside, but appearances can be deceiving.

Someone dressed extravagantly (wearing designer labels like Louie Vuitton and Chanel) may look rich on the outside, but can actually be loaded with thousands of dollars of debt. Someone with tattoos all over their face may come off as scary and unapproachable, but they actually may be the nicest person around.

Therefore know your own prejudices and what they are when you photograph. Realize that no photograph is truly objective, and that your photographs are more of a reflection of yourself than the subject. However if you wish, strive to get to know more about your subjects. If you take a photograph of someone candidly and without their permission, perhaps approach them afterwards and chat with them and get to know their personal or life story.

I am currently working on a project titled: “Suits” – my critique on the corporate world and I see the suit as a symbol of oppression. Of course this is my biased view of suits (a lot of people really like wearing suits). Therefore although I am selectively trying to capture photographs of suits looking miserable, I have taken lots of photos of suits looking proud. Sometimes I ask for permission – other times I do it more candidly. However at the end I still try to chat with them about what they do for a living, how they enjoy their work, in order to better understand their stories (compared to my outsider observations).

3. Create specific photographs

When we are shooting street photography, we tend to wander and take photos of anything that interest us. However my personal view (and that of Diane Arbus) is that being very specific when you are out shooting is important- to make a stronger message in your photographs:

“A photograph has to be specific. I remember a long time ago when I first began to photograph I thought, There are an awful lot of people in the world and it’s going to be terribly hard to photograph all of them, so if I photograph some kind of generalized human being, everybody’ll recognize it. It’ll be like what they used to call the common man or something.

It was my teacher Lisette Model, who finally made it clear to me that the more specific you are, the more general it’ll be. You really have to face that thing. And there are certain evasions, certain nicenesses that I think you have to get out of.

On the streets there are so many things to photograph. But we have to be selective. There has to be a reason why we decide to take a photograph of let’s say a little kid skipping in a puddle versus taking a photograph of an old person sitting in a wheelchair.

General photographs tend to be quite boring. If you are more specific in your approach in terms of either your subject matter or approach, not only will your photographs have a stronger collective strength – but they will have more power and meaning to the viewer.

However Arbus shares a problem of trying to be very specific when we are photographing — namely that it can be quite harsh:

The process itself has a kind of exactitude, a kind of scrutiny that we’re not normally subject to. I mean that we don’t subject each other to. We’re nicer to each other than the intervention of the camera is going to make us. It’s a little bit cold, a little bit harsh.

Now, I don’t mean to say that all photographs have to be mean. Sometimes they show something really nicer in fact than what you felt, or oddly different. But in a way this scrutiny has to do with not evading facts, not evading what it really looks like.

When you are specific when you are photographing, you are putting emphasis or a level of exactitude of certain parts of your subjects. For example, you might highlight the glasses on their face, their weathered hands, or the fact that they might be in a wheelchair. This is what you choose to show (or not to show) by framing your camera in a certain way, or even using a certain depth-of-field.

Takeaway point:Realize that as street photographers, we aren’t always going to show our subjects in the most flattering light. After all, life isn’t always flattering. As Arbus explains, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you h”have to be mean” — but follow your gut and your heart. Strive what feels authentic to you.

4. Adore your subjects

When you take photographs, select your subjects based on what interests you. In Arbus’ example – she was drawn to “freaks” (I’m certain that the term was more politically correct 40 years ago). She explains that she adored them, and found them compelling:

“Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me. I just used to adore them. I still adore some of them, I don’t quite mean they’re my best friends but they made me feel a mixture of shame and awe.

Theres a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.”

One of the unique parts of Arbus’ work is that she approached subjects that nobody else was really photographing at the time. However rather than just looking at the “freaks” as despicable members of society – she made them human. She explains not only did they excite her, but she found a sense of honor in them – calling them “aristocrats”. After all, they had to deal with much more difficulties in life that us “regular people” often don’t have to. She saw them in a different way than the average person – as venerable.

Takeaway pointEveryone is drawn to a certain type of subject. You might be interested in photos of couples, photos of people jubilant, depressed, photos of children, the elderly, and so on.

I feel it is important to be compassionate to the subjects that you photograph. However once again, we all have our natural prejudices when we photograph – and our photos may not always be so compassionate.

If you also approach a certain subject matter and you want to be unique – don’t just see it how the rest of society sees it. For example children are generally seen as adorable and cute things. Why not try to do the opposite and show them as creatures that can be menacing? Elderly people are generally seen as old and grumpy. Why not take photographs that make them look gentle and compassionate?

Make sure whatever or whoever you photograph that you are passionate about it. Treat your subjects with respect, and know the power of distortion that your lens can have.

5. Gain inspiration from reading

have written about this in the past, how in order to be more creative with our photography it is important to consume inspiration from places outside of photography. Arbus shares that where she gained some of her inspiration was from reading:

“Another thing I’ve worked from is reading it happens very obliquely. I don’t mean I read something and rush out and make a picture of it. And I hate that business of illustrating poems.

But here’s an example of something I’ve never photographed that’s like a photograph to me. There’s a Kafka story called “Investigations of a Dog” which I read a long, long time ago and I’ve read it since a number of times. It’s a terrific story written by the dog and ts the real dog life of a dog.

Actually, one of the first pictures I ever took must have been related to that story because it was a dog. This was about twenty years ago and I was living in the summer on Martha’s vineyard. There was a dog that came at twilight every day. A big dog kind of a mutt. He had sort of a Weimaraner eyes, grey eyes. I just remember it was very haunting. He would come and just stare at me in what seemed a very mythic way. I mean a dog, not barking, not licking, just looking right through you. I don’t think he liked me. I did take a picture of him but it wast very good.

I don’t particularly like dogs. Well, I love stray dogs, dogs who don’t like people. And that’s the kind fo dog picture I would take if I ever took a dog picture.”

Arbus shares this example that from reading a book by Kafka of a dog- she was able to see something in real life that sparked her imagination. Although she didn’t take a great photograph, it was still a great example of how she was able to gain outside inspiration and apply it to her photography

Takeaway pointCreativity and gaining insights into your photography often come from outside sources. Don’t just consume images from street photography, but diversify. Look at paintings, sculpture, read books, and listen to music. You can never know when one of these outside pieces of inspiration can give your photography a boost of creativity.

6. Utilize textures to add meaning to your photographs

As photographers we can often get obsessed with “the look” of our photographs. We experiment with different focal lengths, shooting at different apertures, using a flash or natural light, color vs black and white, formats, and so forth. However rather than just experimenting for the aesthetic quality, Arbus feels that using different techniques should be for adding meaning.

Arbus shares her experiences in trying to create textures in her image to convey more meaning, rather than just being textured for the sake of being textured:

“In the beginning of photographing I used to make very grainy things. I’d be fascinated by what the grain did because it would make a kind of tapestry of all these little dots and everything would be translated into this medium of dots. Skin would be the same as water would be the same as sky and you were dealing mostly in dark and light, not so much in flesh and blood.

But when I’d been working for a while with all these dots, I suddenly wanted terribly to get through there. I wanted to see the real differences between things.

I’m not talking about textures. I really hate that, the idea that a picture can be interesting simply because it shows texture. I mean that just kills me I don’t see whats interesting about texture. It really bores the hell out of me.

But I wanted to show the difference between flesh and material, the densities of different kinds of things air and water and shiny. So I gradually had to learn different techniques to make it come clear. I began to get terribly hyped on clarity.”

For Arbus’ earlier work she started with a Nikon 35mm camera, but in order to better achieve her creative vision she switched to a TLR Rolleiflex – in which she worked the square format and achieved extra detail in switching from small to medium-format.

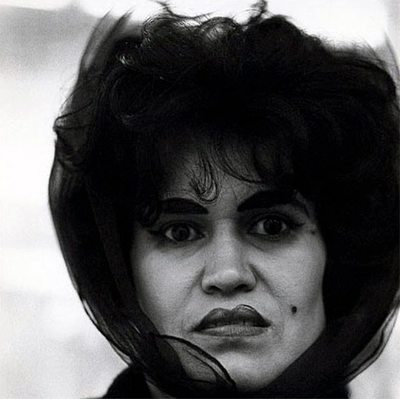

Arbus also worked quite a bit with flash, which brought out more textures and light in her photographs. Many of her photographs taken during the day (such as the photograph of the woman with the veil above) show that she balanced the fill flash and the background light – creating a quite surreal effect. Not only that, but it better brought out the texture in the woman’s face, the fabric of the veil, and of her light-colored hair and fur coat.

Takeaway pointWhen you decide to use a certain camera, focal length, flash vs natural light, black and white versus color, etc — think about the added meaning you want to give to your photographs. For example, if you use a 28mm lens (rather than a 50mm lens) consider why you are trying to do that. Instead of just making more distortion for the sake of it — perhaps you should use it to create a more sense of immediacy and intimacy with your subject. When shooting in black and white – are you trying to document something sad and depressing or want to focus on forms and shapes? If working in color- what about the color adds meaning to your photographs?

Experiment freely with your photography, but don’t get carried away for trying something new for the sake of trying something new and trying to be different. Think about the meaning you will add to your images.

7. Take bad photos

As photographers, we all hit plateaus or feel lack of inspiration at times. How do we get over this? Arbus suggests the idea of purposefully trying to “take bad photos”:

“Some pictures are tentative forays without your even knowing it. They become methods. It’s important to take bad pictures. It’s the bad ones that have to do with what you’ve never done before. They can make you recognize something you had seen in a way that will make you recognize it when you see it again.

By forcing ourselves to take bad photographs, it will cause us to understand what makes a good photograph. Also when looking at our bad photographs, we can learn how to improve on our pre-existing photography.

Arbus also discounts the importance of composition in her photography:

“I hate the idea of composition. I don’t know what good composition is. I mean I guess I must know something about it from doing it a lot and feeling my way into and into what I like. Sometimes for me composition has to do with a certain brightness or a certain coming to restness and other times it has to do with funny mistakes. Theres a kind of rightness and wrongness and sometimes I like rightness and sometimes I like wrongness. Composition is like that.”

Looking at Arbus’ photographs, I would say that they are well-composed. She fits her subjects well in the frame, and positions them which give the images a sense of balance and harmony.

However she also mentions an important point that sometimes good compositions come from funny mistakes. Good compositions (although they should be intentional) can sometimes be unintentional.

Takeaway pointComposition is very important in street photography – as it helps the viewer understand who the subject in your photograph is. Not only that, but there is a natural sense of balance and beauty in composing something well.

There are lots of photographs you are going to take that are bad. They are either going to be boring or poorly composed.

However learn from your mistakes, and realize that making mistakes is part of the creative process. Without making bad photographs, how would we know what are our good photographs?

8. Sometimes your best photos aren’t immediately apparent (to you)

I believe that photographers (myself included) are awful editors of their own work. We often get emotionally attached to our images, and can often take our bad photographs as good photographs. On a similar vein, we can also overlook our best photographs and not realize that they are interesting. Arbus explains this more in-depth:

“Recently I did a picture—I’ve had this experience before—and I made rough prints of a number of them, there was something wrong in all of them. I felt I’d sort of missed it and I figured id go back. But there was one that was just totally peculiar. It was a terrible dodo of a picture. It looks to me a little as if the lady’s husband took it. Its terribly head-on and sort of ugly and there’s something terrific about it. I’ve gotten to like it better and better and now I’m secretly sort of nutty about it.”

First impressions aren’t always everything. When we first look at our photographs, we may not see anything interesting. However once we sit on them- and think about them some more, they can become more interesting over time.

Takeaway pointI feel it is always important to get a second-opinion on your photographs. If you took a photograph that you think is interesting – your own judgement may not always be the best. Ask people you trust and respect for their feedback both online and offline. Ask them both what they like and what they dislike about the photograph, as they are less attached to the photograph than you and can give you more honest feedback.

9. Don’t arrange others, arrange yourself

One of the great appeals of street photography is that there is little we can arrange. Arbus shares that when she photographs people, she prefers to arrange herself instead of her subjects:

“I work from awkwardness. By that I mean I don’t like to arrange things if I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself”.

I like to take lots of candid photos, but I also like to take photos when I arrange my subjects in a certain way I’d like to capture them. However it is true that the most interesting photos I have taken are generally the ones that aren’t posed.

Takeaway pointIf you want to make an interesting photograph of someone but you don’t want to arrange them in a certain way or ask them to pose for you – arrange yourself in a different way. Take a photo of your subject form different angles – form the left, head-on, and from the right. Crouch, or stand up. Change your positioning which will help give the scene a better sense of clarity.

10. Get over the fear of photographing by getting to know your subjectsGetting over your fear of shooting street photography is one of the biggest challenges all of us face. If you decide to photograph a certain location over and over again, it may be a good idea to get to know the community and your subjects to overcome that fear. Arbus shares her experiences shooting outsiders at a park:

“I remember one summer I worked a ltot in Washington Square Park. It must have been around 1966. The park was divided. It has these walks, sort of like a sunburst, and there were these territotries stalked out. There were young hippie junkies down one row. There were lesbians down another, really tough amazingly hard-core lesbians and in the middle were winos. They were like the first echelon and the girls who came from the Bronx to become hippies would have to sleep with the winos to get to sit on the other part with the junkie hippies.

It was really remarkable. And I found it very scary. I mean I could become a nudist, I could become a million things. But I could never become that, whatever all those people were. There were days I just couldn’t work there and then there were days I could.

And then, having done it a little, I could do it more. I got to know a few of them I hung around a lot. They were a lot like sculptures in a funny way. I was very keen to get close to them, so I had to ask to photograph them. You cant get that close to somebody and not say a word, although I have done that.”

Diane Arbus often describes herself as being quite awkward and shy when photographing. She had her doubts, fears, and concerns when photographing. The interesting thing to note is that most of her photos are very upfront and close to her subjects.

Therefore to overcome her fear of shooting these people in the park (who frightened her) – she would revisit over and over again, and found out over time she became less timid. Not only that but she got to know the people there, and asked for permission. This helped her feel more comfortable and photograph the people in the area.

Takeaway pointWe all have a certain degree of fear when it comes to shooting street photography. Know that everyone has it.

There are many ways to get over the fear of shooting street photography (download a copy of my free e-book on overcoming your fear of shooting street photography here). However know that naturally the more you shoot street photography the more up-front and honest you are about it, you will become more comfortable over time. I can speak from experience that I am definitely more comfortable shooting street photography now than I was around two years ago.

Don’t also be ashamed to ask for permission. If you feel uncomfortable and want to take a photograph, just ask for permission. The worst that will happen is that they will say no, and you simply move on. The best thing that can happen is that they will say yes- and you will build that connection.

11. Your subjects are more important than the pictures

Although Arbus was criticized much during her lifetime (and even now today) for being uncompassionate – she certainly did care for her subjects more than the photos themselves:

“For me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture. And more complicated. I do have a feeling for the print but I don’t have a holy feeling for it. I really think what it is, is what its about. I mean it has to be of something. And what its of is always more remarkable than what it is.”

Arbus explains how for her the subject of the photograph is more important (and often more interesting) than the photograph itself. She explains that the photos can be interesting, but she doesn’t get that same “holy feeling” she gets with her subjects.

Takeaway pointAs street photographers we strive to take interesting photos. But remember to not let that overshadow the importance of your experiences and connections with your subjects.

Know that human beings are both more interesting and important than just images of them. Photos are two-dimensional while people are three-dimensional to them. Photos are mute while people can speak about their experiences.

Conclusion

© Estate of Diane ArbusDiane Arbus was not only an incredible photographer, but she also had deep feelings and emotions with her subjects – which I feel come across in her photography. She truly followed her heart in her photography, and took photos of subjects that both interested her – and that she felt compassion and warmth to.

As street photographers we can relate much with the types of photos that Arbus took (as many of them were on the street). Although we can learn much from the images that she shot, we can learn more from her personal philosophy around why she took the photos the way she did- and even her approach.

Don’t be shy to ask for permission, and get close and intimate with your subjects. You may have natural fears approaching people (as all of us do) – but photograph openly, honestly, and from the heart. People may criticize you for what you do, but as long as you follow your own moral compass- ignore what others have to say.

To see the entire introduction to the Aperture Monograph of Arbus’ life, click here.

11 Lessons Diane Arbus Can Teach You About Street Photography

"(All photographs copyrighted by the Estate of Diane Arbus)

Diane Arbus is a photographer that has a very profound impact on me. When I first saw her photograph of the “grenade kid” — it hit me in the chest and has burned itself in my mind ever since. Upon studying more of Diane Arbus’ work — I found her photographs to be very applicable to my interest in shooting street photography of strangers- mostly as a mode of portraiture.

There is a wealth of knowledge on Diane Arbus (several memoirs, books, and even movies have been made on her), and I cannot say I am an expert on her work. However here is some golden knowledge I have found from one her books published by Aperturethat I found incredibly insightful that I wanted to share with you." http://erickimphotography.com/blog/2012/10/15/11-lessons-diane-arbus-can-teach-you-about-street-photography/

1. Go places you have never been

2. The camera is a license to enter the lives of others

3. Realize you can never truly understand the world from your subjects eyes

4. Create specific photographs

4. Adore your subjects

5. Gain inspiration from reading

6. Utilize textures to add meaning to your photographs

7. Take bad photos

8. Sometimes your best photos aren’t immediately apparent (to you)

9. Don’t arrange others, arrange yourself

10. Get over the fear of photographing by getting to know your subjects

11. Your subjects are more important than the pictures

Biography: Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus changed how the world looks at photographs and how photographs look at the world. Best known for her pictures of “freaks” and eccentrics such as “The Jungle Creep,” “The Marked Man,” and nudists, she also changed the world of children’s fashion photography and celebrity photography. She was alternately described as shy, sweet and girlish or coldly aggressive and ”as tough as any man” in her field. Friends and colleagues were amazed by her ability to relate to her subjects, her openness and vulnerability with them. On the other hand, some people who posed for her found her to be manipulative, bossy, and cold. In a 1985 article titled “The Hostile Camera,” Calvin Bedient said of her: “She is a modernist heroine, braving the dark places of psychology, her only shield her camera, an eye that would not flinch.”

Diane was born on March 14, 1923, to Gertrude and David Nemerov. She was the second of three children, between elder brother Howard and younger sister Renee. All the Nemerov children grew up surrounded by the trappings of wealth and success. Their maternal grandparents started the Russeks fur stores their father now ran. Their only contact with their father’s side of the family (the poor immigrant Nemerovs) was when they would spend Passover in Brooklyn with David Nemerov’s parents. Later in life, Diane would frequently refer to the atmosphere of wealth in which she grew up. “I was confirmed in a sense of unreality. All I could feel was my sense of unreality,” she told interviewer Studs Terkel (in 1969) Her later career could be summed up as a constant search for the “reality” she was forbidden to see as a child.

Diane and her siblings attended the Ethical Culture School and the Fieldston School, both in Manhattan. At fourteen, Diane met nineteen-year old-Allan Arbus, who was working in the Russeks art department. They immediately fell in love and became intensely involved with one another. Though her parents tried to discourage the affair, (much as her grandparents had tried to stop her parents), Diane and Allan continued to meet clandestinely for the next four years. On April 10, 1941, when she was just eighteen, Diane and Allan Arbus were married by a rabbi. Her parents, faced with this fait accompli, gave their blessing to the marriage. The Arbuses were married for twenty-eight years, although they separated after nineteen, and had two children, Doon and Amy.

In 1946, after Allan returned from World War II, the couple decided to pursue a career as fashion photographers. David Nemerov gave them their first job, the account with Russeks Furs. Over the next ten years the Allan and Diane Arbus Studio became very successful, with Diane conceiving the style of the shoot and Allan handling the technical side. Allan, for his part, always encouraged Diane to take her own pictures and pursue her own creativity. Diane herself credited Allan as being “my first teacher.” However, Diane hated the world of fashion photography and began to suffer increasingly from depression (as had her mother). In 1957, she quit styling the Arbus Studio photo shoots.

Moving into the world of independent photography was not easy for her. Diane Arbus was extremely shy, which hampered her ability to approach strangers on the street to ask them to pose. In addition, pursuing her own career went against the model of women at the time. As her daughter Amy has remarked: “Ma had always thought all her life was about helping Pa do his thing. It took her a long time to adjust.”

By 1960, Diane and Allan Arbus had separated, though Allan continued to be a major emotional support in her life. He also continued to assist Diane with her photography and taught her the technical side of the art.

To develop herself as a photographer, Arbus first enrolled in Alexey Brodovitch’s workshop, but she quit soon after she started. Her next attempt was more successful. In 1958 she enrolled in Lisette Model’s class at the New School. In Model, Arbus found her mentor and a lifelong friend. Model helped her identify and accept what subjects she wanted to photograph—what Doon Arbus later called “the forbidden.” Art critic Peter Bunnell has said that Arbus “learned from Model that in the isolation of the human figure one can mirror the essential aspects of society.”

In 1959, she met her second mentor, Marvin Israel, and he quickly became one of the major influences in her life. He supported her ideas and pushed her to pursue them even further. He advised her on which photograph to choose from a contact sheet and introduced her to people he thought would influence her or help her career. In 1961, he became the art director of Harper’s Bazaar and was able to publish her work as well.

Perhaps because of Model’s and Israel’s support, Arbus began to use her fear as opposed to being frozen by it. Throughout the rest of her life she would talk of her photography as an adventure and the fear as a stimulus. Her biographer Patricia Bosworth notes, “Her terror aroused her and made her feel; shattered her listlessness, her depression. Conquering her fears helped her develop the courage she felt her mother had failed to teach her.” Driven by her curiosity and fear, Arbus began to haunt the places that would define her as a photographer: Hubert’s Freak Museum in Times Square, Coney Island, gay nightclubs, and the tenements of Brooklyn and Manhattan. She began her life as a self-described “collector,” viewing her work as “a sort of contemporary anthropology.”

In the late summer of 1959, Arbus took her portfolio to Esquire magazine and showed it to Harold Hayes, the articles editor. Hayes was “bowled over by Diane’s images. … Her vision, her subject matter, her snapshot style were perfect for Esquire, perfect for the times; she stripped away everything to the thing itself. It seemed apocalyptic.” A few months later, Arbus was asked to do a photo essay on the nightlife of New York for a special Esquire issue on the city, published in July 1960. It contained Diane Arbus portraits of six “typical” New Yorkers, titled “The Vertical Journey: Six Movements of a Moment Within the Heart of the City.”

“The Vertical Journey” marked the beginning of her career as a solo commercial photographer. Over the next eleven years Diane Arbus would publish over 250 pictures in more than seventy magazine articles. Her most frequent supporters in the publishing world were Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, and two London publications, the Sunday Times Magazine and Nova. Her work also appeared in New York, Show, Essence, the New York Times, Holiday, Sports Illustrated, and the Saturday Evening Post.

Throughout her career Diane Arbus hoped to break the pattern that bound most photographers. She tried to make a living from magazines while still maintaining her integrity and pursuing her style and interests, and to some degree she succeeded. Her serious art work and her magazine work were never as separate and distinct as that of most other photographers.

As the magazine assignments and her friendships with Lisette Model and Marvin Israel began to help Arbus feel more confident, she developed her own singular approach to photography, both artistically and technically. In 1962, Arbus changed her camera from a Leica to a Rolleiflex. The negatives were less grainy and gave her the clarity she wanted. The square frame of this new camera became a signature of her later work. In 1964, she began using a Mamiya C33 camera along with her Rollei. She used the Mamiya with a flash, which gave her subjects the exposed and vulnerable look that became another signature of her style. By 1970, she was taking photographs with a Pentax.

In 1965, three of Arbus’s early pictures were included in a show at the Museum of Modern Art called “Recent Acquisitions.” Arbus was hesitant and concerned, as she would be throughout her career, about the public’s reaction. She was right. Yuben Yee, the photo department’s librarian, would come in early every morning to wipe the spit off the photos. When Arbus learned of this, she left town for several days. As Yee said, “People were uncomfortable—threatened—looking at Diane’s stuff.”

Over this period, Arbus was getting work from magazines to do portraits of the famous and a few children’s fashion shoots. She also received two Guggenheim Fellowships, in 1963 and 1966, to pursue her private work. While still taking photos of “freaks” and eccentrics, she was moving into other areas of identity. She began taking pictures of twins and triplets, of families and couples in Central Park, of the uptown and downtown art scenes and of nudist camps.

In 1967, the Museum of Modern Art asked Arbus to contribute to “New Documents,” a major exhibit of modern photography. Again, she was hesitant about putting her work on public display. At the same time, she became tremendously excited by the possibility for future work, which she hoped the exhibit might generate.

The critical response was generally positive, although Chauncy Howell of Women’s Wear Daily called it “grotesque.” Robert Hughes of Time said, “Arbus is highly gratifying.” In the New York Times, Jacob Deschin wrote, “Even her glamour shots … look bizarre. … At the same time there is occasionally a subtle suggestion of pathos, now and then diluted slightly with a vague sense of humor. Sometimes, it must be added, the picture borders close to poor taste.”

Unfortunately, although the “New Documents” exhibit did bring Arbus to the attention of the London Sunday Times Magazine, her fear that the exhibit might lead to the public misunderstanding her work was realized. With the notoriety of the “New Documents” show, Diane Arbus became more firmly established as the “freak” photographer, and publishers became increasingly shy of using her to photograph the subjects of their stories. A further blow to her commercial career came with the controversy over the “Viva pictures.”

In December 1967, Arbus was hired by the newly created New York magazine to photograph the actor Viva. Arbus ultimately gave the magazine several nude photographs of Viva, which were published in the April 29, 1968, issue. Viva, who felt she had been misled and lied to by Arbus, threatened a lawsuit but later dropped it. The public and advertisers were so upset that the magazine lost over a million dollars in advertising, most of which never returned to the publication. Journalist Tom Morgan says that those pictures were “watershed pictures. They broke down the barriers between private and public lives.”

In 1968, she was hospitalized with hepatitis. (She had suffered from it before, in 1966.) Weakened from the illness, she felt that she was losing her strength and independence. She became increasingly depressed. In 1969, her marriage to Allan Arbus was formally ended by divorce and the Arbus Studio was closed.

By 1970, Diane Arbus had become a legend among young photographers. She was teaching classes and workshops and giving lectures—generally not something she enjoyed, but she was in demand and needed the money. That year she won the Robert Levitt Award from the American Society of Magazine Photographers for outstanding achievement. She also began what would be one of the final projects of her career, taking pictures of mentally retarded adults at a home in Vineland, New Jersey. At first these photos seemed to exhilarate her, but soon she grew to hate the Vineland pictures, because she felt that the shots were “out of control.”

Beyond her dismay over those photographs, there was the attention brought on by success. The May 1971 issue of ArtForum had published a portfolio of her pictures. Walter Hopps of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., had persuaded her to agree to exhibit her work at the Venice Biennale in the summer of 1972. These projects only seemed to panic and depress her further. “She did say over and over again that now that she was getting better known people expected things of her and she didn’t want anyone to expect things from her since she didn’t know what to expect from herself and never would.”

Suffering from extreme depression, caught between her fear of fame and her need for money, and at a crossroads in her work, Diane Arbus committed suicide in her apartment on July 26, 1971, leaving the words “last supper” written across that date in her journal. Marvin Israel discovered the body on July 28.

A posthumous exhibit was mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972, then traveled around the United States and Europe. In 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of New York mounted a major, comprehensive retrospective exhibition, entitled “Diane Arbus Revelations.” Since her death three books of her photographs have been published: Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, Diane Arbus: Magazine Work, and Untitled. For many years she remained a cult figure, and it was not until the 1980s that her work came to be generally accepted. Her impact and influence will never again be considered marginal. She changed not only photography but how we identify each other as human beings.

BibliographyArbus, Doon, and Marvin Israel, eds. Diane Arbus: Magazine Work (1984); Bedient, Calvin. “The Hostile Camera: Diane Arbus.” Art in America (January 1985); Bosworth, Patricia. Diane Arbus (1984); Bunnell, Peter. “Diane Arbus.” Print Collectors Newsletter (January/February 1973); Deschin, Jacob. “People Seen as Curiosity.” NYTimes, March 5, 1967, sec. 2, p. 21; Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (1972); Morgan, Susan. “Loitering with Intent: Diane Arbus at the Movies.” Parkett 47 (1996); NAW modern; Spring, Justin. “Diane Arbus.” ArtForum (February 1992).

11 Lessons Diane Arbus Can Teach You About Street Photography

(All photographs copyrighted by the Estate of Diane Arbus)

Diane Arbus is a photographer that has a very profound impact on me. When I first saw her photograph of the “grenade kid” — it hit me in the chest and has burned itself in my mind ever since. Upon studying more of Diane Arbus’ work — I found her photographs to be very applicable to my interest in shooting street photography of strangers- mostly as a mode of portraiture.

There is a wealth of knowledge on Diane Arbus (several memoirs, books, and even movies have been made on her), and I cannot say I am an expert on her work. However here is some golden knowledge I have found from one her books published by Aperturethat I found incredibly insightful that I wanted to share with you.

Diane Arbus is a photographer best known for her square-format photographs of marganlized people in society — including transgender people, dwarfs, nudists, circus people. Although she has always expressed love for her subjects, her work has always been controversial and critiqued heavily by art critics and the general public for simply being “the photographer of freaks” and casting her subjects in a negative light.

Arbus studied photography under Berenice Abbott, and Lisette Model, during the period when she started to shoot primarily with her TLR Rolleiflex in the square-format she is now famous for. Most of her photographs are shot head-on, mostly with consent, and often utilizing a flash to create an surreal look.

Arbus was born in 1923, and it shocked the entire photographic community when she committed suicide in 1971 (at the age of 48). It was reported that she did experience many “depressive episodes” during her life.

Although it has been around 40 years since her passing, she has influenced countless photographers (including myself) and there is still much work being published on her life. In 2006, Nicole Kidman played as Diane Arbus in the motion picture “Fur” — a fictional version of her life story. Also recently published (2011) a psychotherapist named William Schultz published a biography on Arbus named: “An Emergency In Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus“.

Lessons from Diane ArbusAll of the excerpts used in this article were from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, in which she shares her thoughts in interviews and writings. You can see an entire selection of the text here:

1. Go places you have never been

When it comes to street photography, I feel one of the greatest joys is that it allows you to experience life in a novel and different way. Arbus shares some of her thoughts:

“My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been. For me there’s spending about just going into someone else’s house. When it comes time to go, if I have to take a bus to somewhere or if I have to grade a cab uptown, it’s like I’ve got a blind date. It’s always seemed something like that to me. And sometimes I have a sinking feeling of, Oh God it’s time and I really don’t want to go. And then, once I’m on my way, something terrific takes over about the sort of queasiness of it and how there’s absolutely no method for control.

I feel that one of the greatest traits that a street photographer has is his or her curiosity. Street photography gives us the wonderful opportunity to have the excuse to go to places we generally don’t go — in order to look for interesting photographs and experiences.

Takeaway point: Explore and take the path off the beaten road. If you always shoot street photography in the same place, venture off elsewhere and go down hidden paths that you haven’t been down before. Realize that there is little you can control in terms of what subjects appear, how your background will look at a given time, and how the weather will be for your shots. Simply let the shots come to you, and embrace them.

2. The camera is a license to enter the lives of others

In street photography, we are often timid to approach random strangers and ask to take photographs of them. After all, it may seem weird for us to simply approach someone we don’t know.

However consider how much weirder it would be to approach a stranger without having a camera and having a reason to talk to them. Having the camera is a license to enter the lives of others, as Arbus explains:

“If I were just curious, it would be very hard to say to someone, “I want to come to your house and have you talk to me and tell me the story of your life.” I mean people are going to say, “You’re crazy.” Plus they’re going to keep mighty guarded. But the camera is a kind of license. A lot of people, they want to be paid that much attention and that’s a reasonable kind of attention to be paid.

Arbus also continues by sharing the idea that many people are quite humbled by being paid a ton of attention by having you want to take their photograph.

Takeaway point:Don’t be embarrassed by your camera and try to hide it when shooting on the streets. Embrace it, and use it as a tool to help you get a license to enter the lives of others. If you see someone on the street that you find interesting and want to get to know more about them — approach them and start chatting with them and explain that you are a photographer and you would like to take their portrait for a project you are working on. Most people become quite humbled by this, and are generally excited to be part of the project.

If you want to take a photograph more candidly, go and take the photograph without permission and then afterwards — explain why you took the photograph. Tell them what project it is for, and what unique part of them that you found that you wanted to capture. When you explain why you think that people are interesting and why you wanted to take a photograph of them, people are generally humbled by that.

3. Realize you can never truly understand the world from your subjects eyes

As a photographer, it is easy to see things from our own perspective. However it is difficult to see the world from your subjects perspective (if not impossible). Arbus explains that although we can try to give our best intents in getting to know our subjects well- our photographs will not always show what we intended. You might have a certain intent when photographing, but the result can be totally different. Not only that, but what we may perceive as a “tragedy” may not be considered as a tragedy to your subject:

“Everybody has that thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way and that’s what people observe. You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw. It’s just extraordinary that we should have been given these peculiarities. And not, content with what we were given, we create a whole other set.

Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you.

And that has to do with what I’ve always called the gap between intention and effect. I mean if you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic. You know it really is totally fantastic that we look like this and you sometimes see that very clearly in a photograph. Something is ironic in the world and it has to do with the fact that what you intend never comes out like you intended it.

What I’m trying to describe is that it’s impossible to get out of your skin into somebody else’s. And that’s what all this is a little bit about. That somebody else’s tragedy is not the same as your own“.

Arbus took a lot of photographs of marginalized individuals in society (transgender, dwarfs, circus people, etc) and of course she had her natural prejudices when she took photographs (as well all do). Her individuals would try to present themselves to the world in a certain way, but other people might perceive them in a different way.

For example, if someone dressed up as a rockstar with chains and spiked studs, they may feel that they are giving off the image that they are powerful and cool. However an outsider might see this as frightening, and something abhorrent.

Takeaway point:Realize that it is impossible to truly get into the mind of someone else. When you are photographing someone in the streets, there is no way to know their entire life history or their character. Sure you might perceive them to be a certain way on the outside, but appearances can be deceiving.

Someone dressed extravagantly (wearing designer labels like Louie Vuitton and Chanel) may look rich on the outside, but can actually be loaded with thousands of dollars of debt. Someone with tattoos all over their face may come off as scary and unapproachable, but they actually may be the nicest person around.

Therefore know your own prejudices and what they are when you photograph. Realize that no photograph is truly objective, and that your photographs are more of a reflection of yourself than the subject. However if you wish, strive to get to know more about your subjects. If you take a photograph of someone candidly and without their permission, perhaps approach them afterwards and chat with them and get to know their personal or life story.

I am currently working on a project titled: “Suits” – my critique on the corporate world and I see the suit as a symbol of oppression. Of course this is my biased view of suits (a lot of people really like wearing suits). Therefore although I am selectively trying to capture photographs of suits looking miserable, I have taken lots of photos of suits looking proud. Sometimes I ask for permission – other times I do it more candidly. However at the end I still try to chat with them about what they do for a living, how they enjoy their work, in order to better understand their stories (compared to my outsider observations).

3. Create specific photographs

When we are shooting street photography, we tend to wander and take photos of anything that interest us. However my personal view (and that of Diane Arbus) is that being very specific when you are out shooting is important- to make a stronger message in your photographs:

“A photograph has to be specific. I remember a long time ago when I first began to photograph I thought, There are an awful lot of people in the world and it’s going to be terribly hard to photograph all of them, so if I photograph some kind of generalized human being, everybody’ll recognize it. It’ll be like what they used to call the common man or something.

It was my teacher Lisette Model, who finally made it clear to me that the more specific you are, the more general it’ll be. You really have to face that thing. And there are certain evasions, certain nicenesses that I think you have to get out of.

On the streets there are so many things to photograph. But we have to be selective. There has to be a reason why we decide to take a photograph of let’s say a little kid skipping in a puddle versus taking a photograph of an old person sitting in a wheelchair.

General photographs tend to be quite boring. If you are more specific in your approach in terms of either your subject matter or approach, not only will your photographs have a stronger collective strength – but they will have more power and meaning to the viewer.

However Arbus shares a problem of trying to be very specific when we are photographing — namely that it can be quite harsh:

The process itself has a kind of exactitude, a kind of scrutiny that we’re not normally subject to. I mean that we don’t subject each other to. We’re nicer to each other than the intervention of the camera is going to make us. It’s a little bit cold, a little bit harsh.

Now, I don’t mean to say that all photographs have to be mean. Sometimes they show something really nicer in fact than what you felt, or oddly different. But in a way this scrutiny has to do with not evading facts, not evading what it really looks like.

When you are specific when you are photographing, you are putting emphasis or a level of exactitude of certain parts of your subjects. For example, you might highlight the glasses on their face, their weathered hands, or the fact that they might be in a wheelchair. This is what you choose to show (or not to show) by framing your camera in a certain way, or even using a certain depth-of-field.

Takeaway point:Realize that as street photographers, we aren’t always going to show our subjects in the most flattering light. After all, life isn’t always flattering. As Arbus explains, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you h”have to be mean” — but follow your gut and your heart. Strive what feels authentic to you.

4. Adore your subjects

When you take photographs, select your subjects based on what interests you. In Arbus’ example – she was drawn to “freaks” (I’m certain that the term was more politically correct 40 years ago). She explains that she adored them, and found them compelling:

“Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me. I just used to adore them. I still adore some of them, I don’t quite mean they’re my best friends but they made me feel a mixture of shame and awe.

Theres a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.”

One of the unique parts of Arbus’ work is that she approached subjects that nobody else was really photographing at the time. However rather than just looking at the “freaks” as despicable members of society – she made them human. She explains not only did they excite her, but she found a sense of honor in them – calling them “aristocrats”. After all, they had to deal with much more difficulties in life that us “regular people” often don’t have to. She saw them in a different way than the average person – as venerable.

Takeaway pointEveryone is drawn to a certain type of subject. You might be interested in photos of couples, photos of people jubilant, depressed, photos of children, the elderly, and so on.

I feel it is important to be compassionate to the subjects that you photograph. However once again, we all have our natural prejudices when we photograph – and our photos may not always be so compassionate.

If you also approach a certain subject matter and you want to be unique – don’t just see it how the rest of society sees it. For example children are generally seen as adorable and cute things. Why not try to do the opposite and show them as creatures that can be menacing? Elderly people are generally seen as old and grumpy. Why not take photographs that make them look gentle and compassionate?

Make sure whatever or whoever you photograph that you are passionate about it. Treat your subjects with respect, and know the power of distortion that your lens can have.

5. Gain inspiration from reading

have written about this in the past, how in order to be more creative with our photography it is important to consume inspiration from places outside of photography. Arbus shares that where she gained some of her inspiration was from reading:

“Another thing I’ve worked from is reading it happens very obliquely. I don’t mean I read something and rush out and make a picture of it. And I hate that business of illustrating poems.

But here’s an example of something I’ve never photographed that’s like a photograph to me. There’s a Kafka story called “Investigations of a Dog” which I read a long, long time ago and I’ve read it since a number of times. It’s a terrific story written by the dog and ts the real dog life of a dog.

Actually, one of the first pictures I ever took must have been related to that story because it was a dog. This was about twenty years ago and I was living in the summer on Martha’s vineyard. There was a dog that came at twilight every day. A big dog kind of a mutt. He had sort of a Weimaraner eyes, grey eyes. I just remember it was very haunting. He would come and just stare at me in what seemed a very mythic way. I mean a dog, not barking, not licking, just looking right through you. I don’t think he liked me. I did take a picture of him but it wast very good.

I don’t particularly like dogs. Well, I love stray dogs, dogs who don’t like people. And that’s the kind fo dog picture I would take if I ever took a dog picture.”

Arbus shares this example that from reading a book by Kafka of a dog- she was able to see something in real life that sparked her imagination. Although she didn’t take a great photograph, it was still a great example of how she was able to gain outside inspiration and apply it to her photography

Takeaway pointCreativity and gaining insights into your photography often come from outside sources. Don’t just consume images from street photography, but diversify. Look at paintings, sculpture, read books, and listen to music. You can never know when one of these outside pieces of inspiration can give your photography a boost of creativity.

6. Utilize textures to add meaning to your photographs

As photographers we can often get obsessed with “the look” of our photographs. We experiment with different focal lengths, shooting at different apertures, using a flash or natural light, color vs black and white, formats, and so forth. However rather than just experimenting for the aesthetic quality, Arbus feels that using different techniques should be for adding meaning.

Arbus shares her experiences in trying to create textures in her image to convey more meaning, rather than just being textured for the sake of being textured: